Mucin Garden – Phil Pool and Jan Whitlock

Mollusc muscle-foot slides, smooth mucin drawn

over labium oris and labia minora.

Spirals and slime

Got plenty of time

No rush

Just hush

Feel the sensuality

Sublime 🐌

Mucin Garden is an art project that includes intimate images of human genitals – it is only suitable for people over 18.

If that is you and you are okay with that, click on the image below to enter.

Watch some snails on Jan’s belly.

Snails and Humans – Behind the Garden Wall

Mucin Garden was inspired by a converstion between me and Jan about how we might work together more colaboratively. Jan mentioned how she had taken photos of snails on a penis and shared the photos with me. As with snails shells, this sent me off in many different spirraling directions.

The more I looked into connections between humans and snails, the more links I found – not least the many references to snails in art and culture.

From medieval manuscripts to 20th C surrealism.

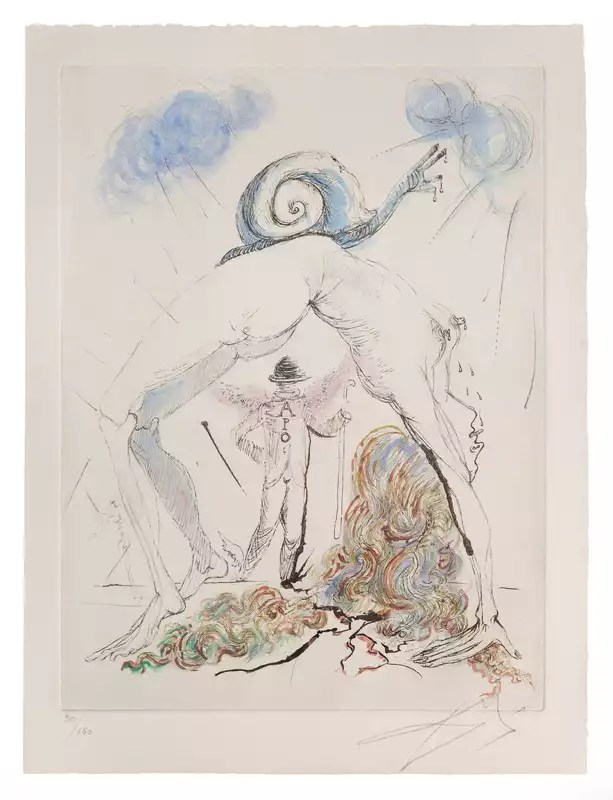

Salvador Dalí featured the snail as a motif as a symbol of both impotence and eroticism: While lobsters were phallic, snails signified impotence but he also linked the snail to the subconscious, sexuality, and eroticism… probably too much Freud.

Salvador Dalí, “Apollinaire” “Woman with Snail”, 1967

Androgyny is a key theme of Bona de Mandiargues’s work linked to the hermaphroditic snaul. Mandiargues sought multiplicity and expansiveness in her life and her work and to free herself from categories or expectations… Her work contains erotic elements with explicit depictions genitalia. ArtUK. – “La lubricità” Bona de Mandiargues (1926–2000)

I had also heard that snails mucin is commonly used in cosmetics. I was not aware of the long history of those and medicinal uses, including wound care, reducing infections and inflamation. There is a great deal of information about this on-line and a particularly clear source is this article in ScienceDirect.

As Jan and I applied the snails to her body for the Mucin Garden photos, we were careful to ensure they were well fed on spinach and cucumber, misted with rain water. They were not asked to slide about on Jan’s body for too long without a break. Essentially, we were as kind to them as we could be.

While picking them up, I paid far more attention to how they move and behave than I ever have before. I can confess to having been quite anti-snails before now. Mainly, I’ve experienced them munching through my young vegetable plants – I’m sorry to say that some have been flung a fair distance. I won’t be doing that now – I’m genuinly fascinated by them.

As we worked, I noted that one that had been put down briefly on a blanket had sectreted a significant amount of mucin into the very absorbant material. I wondered how much more mucin, and thereby, water resource intensive, it must be for them to move on such materials. This inspired me to consider how mucic is “harvested” for cosmetic purposes.

While I was briefly attracted to the medical and other benefits of mucin, I am very much put off by the often cruel ways that mucin is taken from snails. Snails will produce more mucin, and it is thought to be with a greater concentration of anti-microbial properties, if they are intentionally stressed. Essentially, in the wild, if injured or they encounter a harmful substance, they will produce more mucin.

This has led to cruel harvesting methods such as injuring snails with sharp points or spraying them with diluate citric acid or salt. There are less cruel methods that involve the snails sliding across materials and the mucin being removed – I’m dubious that the low quantities produced won’t encourage producers to be more exploitative.

There is, however, little evidence that it is worthwhile (certainly not for the snails) of using mucin for cosmetic treatements. Like so much of the beauty industry, it is yet another way to make people feel self-conscious about their appearance and to extract money from us.

Join in by contacting me via my contacts page.